|

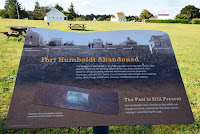

| Image from the Library of Congress |

There are occasions when you find you have some time on your

hands. Then you realize how long it has been since you did certain things. Like, write

in your blog. Everyone has the pandemic on their mind so I might as well tell

you my story so far.

This January I started a new teaching job with an alternative

education high school that partners with a nonprofit organization that provides

flight instruction to the students. More about that later, but in summary, I

teach high school level history, math, and aviation science (which is basically

private pilot ground school). Since February we’ve been telling our students

about the approaching pandemic and personal precautions to take. We stopped our

ritual of shaking hands with each student every morning and opted instead for

fist and elbow bumps. At the end of my unit on the First World War, I taught a

class on the 1918 Flu Pandemic that included showing the American Experience documentary. New info for most; I can honestly say I had their attention on

that one.

On Friday, March 13th we were off for the end of

the quarter when my principal contacted me and said there would be no students

the following week and that we would come in and figure out how we were going to

teach online for the next couple of weeks. Before the weekend was over, I was

told that teachers would be required to stay home as well. Now we are planning

lessons to be provided online and provide work to be assigned through Google Classroom. We

haven’t implemented yet, because now we must figure out how to get a computer

and Internet access to every student. Except for trips to the grocery store and

taking Elvis the corgi for a walk, we’ve been staying home since the 13th.

More to follow.

Write Down Your Story.

I don’t know if being well versed in history is good or bad.

Because now we’re wondering just how bad this pandemic is really going to be or the

economic situation that will follow. And we have some events in our history

that we can use as a cautionary tale. Sheila and I both agreed that we thought

we’d never live to see a cataclysmic event like the 1918 Influenza Pandemic or the Great

Depression. Now I’m wondering if I might see something similar to both. Then I realized that we have

seen some major things in our lifetime. Two I can think of are the fall of the Berlin Wall and 9/11. We got past those and others. They are now in our memory,

in some cases like it happened yesterday, and as if it were ancient history to younger

generations.

I can tell you one thing. As a reader, researcher, and writer of

history, I thank the people who recorded their experiences during challenging times.

Like the University of Virginia history professor Herbert Braun says, “We do not write alone.” For me, it means that writers of history need your help. Future generations will

want to know the personal, emotional toll that this event had on you and your

friends and family. Even more basic is what was it like in your local area?

What did you do to stay safe and sane?

Please, write your stories down. Keep a journal. Record a

video. Get the kids involved too. If they are young, they can draw pictures. No

detail is too mundane. Don’t lose your thoughts to social media. Keep copies of

what you post in your own files. Some day they are going to be gold to your

descendants. And to someone like me.

Please, write your stories down. Keep a journal. Record a

video. Get the kids involved too. If they are young, they can draw pictures. No

detail is too mundane. Don’t lose your thoughts to social media. Keep copies of

what you post in your own files. Some day they are going to be gold to your

descendants. And to someone like me.

P.S. If you need a good book recommendation, a few years ago

I read “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Greatest Pandemic in History” by John M. Barry. It stuck with me and a good read considering our current times.