Hannah Duston's Capture and Escape from the Indians

|

The Hannah Duston statue is in

Haverhill, Massachusetts. |

I did not make a special post for Women’s History Month last

March. But I should have written about

Hannah Duston (or sometimes it’s spelled

Dustin). When I told my wife about Duston

- the

first woman in the United States to have a statue erected in her honor

- she said, “This woman

sounds like a badass.” I’d have to agree with that, based simply on her story.

But the memory of Hannah Duston is also an example of how we interpret our history

through the years.

I really enjoy it when I catch myself in some preconceived notion.

When you think of Puritan settlers in 1600s Massachusetts, do you think of a

bunch of devoutly religious, passive people, kind of like the pilgrim mythology?

Me too! Then while I was on the west coast, I read the story of Hannah Duston

in the book “Massacre on the Merrimack: Hannah Duston's Captivity and Revenge

in Colonial America” by Jay Atkinson. That book dissuaded me from my

preconceptions and when we were recently passing through Massachusetts, I just

had to take a look at the area where this story took place.

|

On the base of the statue you'll

find a panel that shows Thomas

Duston defending his children. |

First, here's the story in a nutshell:Haverhill, Massachusetts, is on the north side of the Merrimack River, just 14

miles west of the Atlantic, or thirty-five miles north of Boston as the crow

flies. Puritan settlers first arrived as early as 1640. Almost fifty years

later, when our story takes place, it was still the edge of civilization,

assuming the perspective of the English settlers. One of those settler families

was the Dustons: Thomas and Hannah and their nine children.

During King William’s War (1688 – 1697), the governor of New

France encouraged Native American tribes to raid English settlements. On March

15, 1697, Abenaki Indians from Quebec, made a raid on Haverhill. A “garrison

house,” that was more heavily fortified (think brick, stone, or heavy logs) than

your average farmhouse was on a hill above the Duston farm, but some distance

away. As they had been instructed, eight of the Duston children headed that way

when they heard the raid begin. Hannah, age 40 at the time, had given birth to

her ninth child a couple of weeks earlier. She had a difficult birth and was

still recovering. Present that morning was a neighbor/nurse, Mary Neff. Husband

Thomas was working on building a brick garrison house of his own about half a

mile away. When he heard the gunfire and whoops of Indians, he mounted his

horse and headed for his house.

|

Another panel shows the killing

of the Indians. |

When Thomas got to his house, he saw Indians heading across

his fields. He knew that they would be able to catch his other children heading

for the garrison house, so he grabbed his rifle and went to get between the

Indians and his kids. Hannah, Mary, and the newborn were to sneak out a back

door and make a run for it on their own. Thomas was successful in blocking the Indians

who were after his kids. They withdrew when Thomas and the children made it to

within rifle range of the three militiamen who were in the garrison house.

Thomas borrowed a fresh horse and headed back with one of the militiamen to

find his wife, but it was too late.

The Abenaki killed 27 colonists and took 14 captives, two of

those were Hannah and Mary. The Indians took them on a speed march away from

any potential pursuers. If any of the captives slowed them down, they were

killed. Hannah’s newborn was stripped from her arms and killed in front of her.

On the trail she and Mary received help in their survival from a fourteen-year-old

boy named Samuel Lennardson who had been taken from Worcester, Massachusetts up

to a year prior and had some modicum of trust from their captors.

|

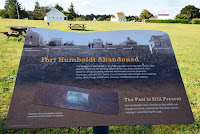

| The Duston Garrison House. |

After weeks on the trail, other captives had all been killed

or traded away. Hannah, Mary, and Samuel were left with a family group of two warriors,

three adult women, and seven children. Along the trail Hannah had, along with

the horrors she had witnessed, been told that her husband and children had all

been killed and that when they arrived at their destination she would be

tortured and either killed or sold into slavery. While camping on an island in

the Merrimack River near present-day Boscawen, New Hampshire, the Indians let

their guard down and all went to sleep. One version says that the warriors

shared a bottle and passed out. Regardless, Hannah enlisted Mary and Samuel to

participate. After the Indians went to sleep, they were able to get ahold of

hatchets. Hannah and Samuel each killed one of the men while they slept. The

three then proceeded to attack the women and children. Hannah left one of the

children alive, a boy who had been kind to her on the trail. He subsequently

fled. One of the women was severely wounded but also escaped. Hannah scalped

the bodies in order to collect a bounty offered by the colony and to prove her

story. The three captives made their escape in one of the Indian canoes,

heading down the river to an English settlement.

The Aftermath

Hannah never wrote down her story, nor did Mary or Samuel. Hannah died in

Haverhill sometime between 1736 and 1738. However, several people have written

the story, claiming that they interviewed Hannah for the details. The most

prominent of these was Cotton Mather. We know that she really did take the

Indian’s scalps because her husband petitioned the government of the Massachusetts

Colony to collect the bounty.

About a hundred years after Hannah’s death, her story was resurrected

and she became a heroine. Some historians believe the story resonated with the

public because of the Indian removal efforts that began in the 1820s. The

first statue in her honor was erected in 1874 in Boscawen, New Hampshire (the site

of her escape). The 35-foot statue depicts her with a hatchet in one hand and

scalps in the other. In 1879 a statue of Hannah was placed in the GAR park in

Haverhill. This one has Hannah holding a hatchet, but she’s pointing with the other hand as if to say, “You were bad.” On the sides of the base are depictions of

the four events in her story: her capture, her husband’s defense of the

children, killing her captors, and returning in a canoe. Today, some question

why Hannah Duston was elevated to hero status, particularly considering that

she killed six children along with the adults, like the tone of this article from Smithsonian. I’m afraid I don’t agree. You just can’t judge someone in

those circumstances through the lens of our modern morality. And although it’s

not right to say “they did it too” as an excuse, one source said that many

of the settlers killed in the Abenaki raid were children. And what about Hannah's newborn?

By the way, the garrison house that Thomas was working on got finished. You can visit it, just outside of Haverhill. Like visiting a Civil War

battlefield, when you’re stopping off at Dunkin’s and fighting the going to

work traffic, it’s hard to visualize what it was like there in the 1600s. The Hannah

Dustin statue and the Duston Garrison House help us remember.

Last week (September 17th) was the 161st

anniversary of the Battle of Antietam. We have visited many times. Antietam, located

next to the small town of Sharpsburg, Maryland, is my favorite Civil War battlefield.

Antietam has historical significance in that the battle has a combined casualty

count of 22,727 killed, wounded, and missing. That makes Antietam (or

Sharpsburg to the Confederates) the highest one-day casualty count in American

military history. It was the impetus for Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation

Proclamation, which changed the Federal cause for fighting the war from

preserving the Union to ending slavery. Moreover, it is an easy battlefield to

view the terrain and understand the flow of the battle. Climb the observation

tower. It’s worth it. And finally, the battlefield park is more than a park or

a tourist attraction. It’s hallowed ground where thousands of Americans fought

and died. That being said, Antietam is also a beautiful place to go for a walk and enjoy

the fall weather.

Last week (September 17th) was the 161st

anniversary of the Battle of Antietam. We have visited many times. Antietam, located

next to the small town of Sharpsburg, Maryland, is my favorite Civil War battlefield.

Antietam has historical significance in that the battle has a combined casualty

count of 22,727 killed, wounded, and missing. That makes Antietam (or

Sharpsburg to the Confederates) the highest one-day casualty count in American

military history. It was the impetus for Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation

Proclamation, which changed the Federal cause for fighting the war from

preserving the Union to ending slavery. Moreover, it is an easy battlefield to

view the terrain and understand the flow of the battle. Climb the observation

tower. It’s worth it. And finally, the battlefield park is more than a park or

a tourist attraction. It’s hallowed ground where thousands of Americans fought

and died. That being said, Antietam is also a beautiful place to go for a walk and enjoy

the fall weather.Enjoy some pictures of the battlefield from our trip last Wednesday.

If you are looking for background on the Battle of Antietam, I have “Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam” by Stephen Sears on my shelf. Get out and

enjoy a historic site while the weather is nice. Maybe I’ll see you at Valley

Forge next week. 😉