View the Index of Unit Histories

"The Bayonet Division"

(Original article written by Jim Broumley, 1/25/2010)

The shoulder sleeve insignia was first adopted in October 1918. It originated from the use of two sevens, one inverted and one upright, to create an hourglass symbol. As a result, the 7th Division was also known as the "Hourglass Division." A bayonet was added to the distinctive unit insignia as a result of the Division's participation in the Korean War and symbolizes the fighting spirit of the 7th Infantry.

The 7th Infantry Division was originally formed for service during World War I. It was activated into the regular army on December 6, 1917, at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, and after training arrived in France in October of 1918, approximately a month before the armistice was signed. Although the 7th Infantry Division as a whole did not see action, many of its subordinate units did. After 33 days in combat, the division suffered 1,988 casualties including 204 killed in action. The 7th Infantry Division returned to the United States in late 1919 and was gradually demobilized at Camp Meade, Maryland. The Division was deactivated on September 22, 1921.

In the buildup for World War II, a cadre was sent to Camp Ord, California to reactivate the 7th Infantry Division on July 1, 1940. The Division was formed around the 17th, 32nd, and 53rd Infantry Regiments and was commanded by Major General Joseph Stilwell. Many of the new soldiers in the Division were draftees, called up in the US Army's first peacetime draft in history.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the 7th Infantry Division was sent to Camp San Luis Obispo to continue training. The 159th Infantry, recently mobilized from the California National Guard, replaced the 53rd Infantry Regiment. From April 1940 until January 1, 1943, the Division was designated the 7th Motorized Division, and the unit trained in California's Mojave Desert. It was thought that the Division would head to North Africa. However, the motor vehicles went away, and the unit was redesignated the 7th Infantry Division once again. Amphibious training began under the tutelage of the Feet Marine Force and General Holland Smith. The 7th Division was now destined for the Pacific Theater.

The Hourglass Division first saw combat in WWII in the Aleutian Islands. On May 11, 1943, led by the 17th Infantry Regiment, elements of the Division landed on Attu Island where Japanese forces were established. The 7th Infantry Division destroyed all Japanese resistance on the island by May 29th after defending against a suicidal "Bonzai" charge. Approximately 2,351 Japanese were killed, leaving only 28 to be taken prisoner. The 7th Infantry Division lost 600 soldiers killed in action. The 159th Infantry Regiment remained on Attu to secure the island and was replaced by the 184th Infantry Regiment. In August of 1943, the 7th Infantry landed on Kiska Island only to find that the Japanese forces there had secretly withdrawn. The Hourglass Division was then redeployed to the Hawaiian Islands for more training.

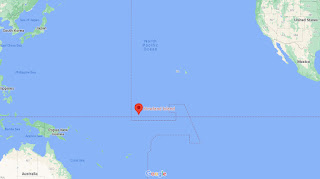

The 7th ID was now assigned to the Marine's V Amphibious Corps along with the 4th Marine Division. Their next stop was Kwajalein Atoll, landing on January 30, 1944. The purpose of Operation Flintlock was to remove all Japanese forces from this group of 47 islands in the Pacific. The 7th Infantry Division landed on the main island of Kwajalein while the Marines moved on to outlying islands. By February 4th the island was under the control of the Hourglass soldiers. The 7th Infantry Division suffered 176 killed in action and 767 wounded.

Elements of the 7th Infantry Division also participated in Operation Catchpole to capture Engebi in the Eniwetok Atoll on February 18, 1944. The islands of that atoll were secured in only a week. Afterward, all elements of the Division were back in Hawaii for refit and training in preparation for the assault on the Philippine Islands. While there, the Hourglass Division was reviewed by General Douglas MacArthur and President Franklin Roosevelt in June 1944.

The 7th Infantry Division was now assigned to the XXIV Corps of the Sixth Army. On October 20, 1944, the Hourglass Division made an assault landing at Dulag, on Leyte in the Philippine Islands. Initially, there was only light resistance. However, on October 26th the enemy launched a large, but uncoordinated counterattack against the Sixth Army. High casualties were suffered in fierce jungle fighting, but the 17th Infantry Regiment took Dagami on October 29th. The 7th Infantry Division then moved to the west coast of the island on November 25th, attacking north to Ormoc and securing Valencia on December 25, 1944. Operations to secure Leyte continued until February 1945. The 7th Infantry Division was then removed from the Sixth Army, which went on to attack Luzon and continue the Philippine Campaign. The Hourglass Division would begin training for their next stop through the Pacific, the Japanese island of Okinawa.

For the landing on Okinawa, the 7th Infantry Division was again assigned to the XXIV Corps, now of the Tenth Army. On April 1, 1945, the 7th Infantry Division landed south on Okinawa along with the 96th Infantry Division, and the 1st, and 6th Marine Divisions. The Okinawa Campaign would eventually have 250,000 troops on the island. The Japanese had removed their armor and artillery from the beach and set up defenses in the hills of Shuri. The XXIV Corps destroyed these forces after 51 days of battle over harsh terrain and in inconsiderate weather. After 39 more days of combat, the 7th Infantry Division was moved into reserve after having suffered heavy casualties. The Hourglass Division was soon moved back into the line and fought until the end of the Battle of Okinawa on June 21, 1945. The 7th ID had experienced 89 days of combat on Okinawa and lost 1,116 killed in action and approximately 6,000 wounded. However, it is estimated that the 7th Infantry Division killed at least 25,000 Japanese soldiers and took 4,584 prisoners.

During WWII, the Hourglass soldiers spent 208 days in combat and suffered 8,135 casualties. The 7th Infantry Division won three Medals of Honor, 26 Distinguished Service Crosses, 1 Distinguished Service Medal, 982 Silver Star Medals, and 3,853 Bronze Star Medals. The Division received nine Distinguished Unit Citations and four campaign streamers.

After the Japanese surrender, the 7th Infantry Division was moved to Korea to accept the surrender of Japanese forces there. After the war, the Bayonets remained as occupation forces in Japan and as security forces in South Korea. During this period, the US Army went through a massive reduction in strength, falling from a wartime high of 89 divisions to only 10 active duty divisions by 1950. The 7th Infantry Division was one of only four drastically under-strength and under-trained divisions on occupation duty in Japan when the North Koreans invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950.

At the beginning of the Korean War, the 7th Infantry Division was further reduced in strength when the Division provided reinforcements for the 25th Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry Division who were sent directly to South Korea. Over the next two months the Bayonet Division was brought up to strength with replacements from the US, over 8,600 South Korean soldiers, and the attachment of a battalion of Ethiopians as part of United Nations forces.

The 7th Infantry Division and the 1st Marine Division made up the landing force for the famous Inchon Landing, code-named Operation Chromite. Supported by the 3rd Infantry Division in reserve the landing began on September 7, 1950, under the command of the X Corps. The operation took the North Koreans completely by surprise and the X Corps immediately moved on to retake the South Korean capital of Seoul. Seoul was captured on September 26th, and the 7th Infantry Division was soon linked with American forces moving north from the breakout of the Pusan Perimeter. The Inchon operation cost the Division 106 killed, 411 wounded, and 57 missing. Casualties of South Korean soldiers with the Division numbered 43 killed and 102 wounded. The X Corps was removed through the ports at Inchon and Pusan to prepare for another amphibious landing further north.

With the North Korean army broken and on the run, the 7th Infantry Division made an unopposed landing at Iwon on October 31, 1950, with orders to move north to the Yalu River with the rest of the X Corps. Through cold, early winter weather, like that only known to a soldier who has been to the Korean Peninsula, the 17th Infantry Regiment made it to Hyesanjin on the Yalu on November 20th. This made the 17th, and as a result the 7th ID, the first American unit to reach the Manchurian border with Communist China.

Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) entered the war on November 27, 1950, storming across the border to attack the Eighth Army in the west and X Corps in the east. Twelve Chinese divisions now assaulted the spread-out regiments of the Bayonets and the rest of X Corps. United Nations forces could not stand up to the onslaught and a retreat was ordered. The 7th ID repulsed repeated attacks as they moved to the port of Hungnam in December of 1950. Three battalions of the division, known as Task Force Faith were trapped by the CCF during the withdrawal. These battalions were wiped out during what became known as the Battle of Chosin Reservoir. During the retreat from the Yalu, the 7th Infantry Division lost 2,657 killed and 354 wounded.

The 7th Infantry Division was back on the front lines in January of 1951 as part of the United Nations offensive to push back the CCF and North Koreans. The Division was now part of the IX Corps and saw action almost continuously until June when it was moved to the rear for rest and refit. The first since coming to the Korean Peninsula. The Bayonets returned to the line in October, now entering the "stalemate" phase of the war. The 7th ID defended a "static line" with the rest of United Nations forces until the armistice. It was only known as "static" because although the enemy was kept above the 38th parallel, very few gains in territory were made. Still, the Bayonets participated in multiple recognizable actions like the Battle for Heartbreak Ridge, the Battle for Old Baldy, the assault on the Triangle Hill complex as part of Operation Showdown, and the famous Battle at Pork Chop Hill.

The Korean War Armistice was signed on July 27, 1953. During the Korean War, the Bayonets were in combat for a total of 850 days. They suffered 15,126 casualties, including 3,905 killed in action and 10,858 wounded. The 7th Infantry Division remained on the DMZ, its headquarters at Camp Casey, South Korea until 1971. On April 2, 1971, the Division was deactivated at Fort Lewis, Washington.

The 7th Infantry Division was reactivated at Fort Ord, California in October of 1974. The Bayonets did not deploy to Vietnam. They were held as a contingency force for South America. On October 1, 1985, the Division was redesignated as the 7th Infantry Division (Light) and organized as a light infantry division. It was the first US division specifically designed as such. During the Cold War the "Light Fighters" trained at Fort Ord, Camp Roberts, Fort Hunter Liggett, and Fort Irwin. The 7th ID now had battalions from the 21st, 27th, and 9th Infantry Regiments.

In December of 1989, the 7th Infantry Division participated in Operation Just Cause, the invasion of the Central American nation of Panama. The 7th Light Infantry Division was joined by the 82nd Airborne Division, the 75th Rangers, Marines, and other US forces totaling some 27,684 personnel and over 300 aircraft. On December 20th, elements of the 7th ID landed in the northern areas of Colon Province, securing the Coco Solo Naval Station, Fort Espinar, France Field, and Colon. The symbolic end of the operation was the surrender of Panamanian Dictator Manuel Noriega on January 3, 1990. Most US units began to return to their American bases on January 12th, however, several units, including the 5th Battalion, 21st Infantry (Light) of the 7th Light Infantry Division stayed in Panama until later in the spring to train the new Panamanian Police Forces.

One final mission for the 7th Infantry Division was helping to restore order to the Los Angeles basin during the riots in 1992. Their deployment was called Operation Garden Plot, whose objective was to patrol the streets of Los Angeles and act as crowd control, supporting the Los Angeles Police Department and the California National Guard. In 1991 the Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommended the closing of Fort Ord due to the high cost of living in the coastal California area. By 1994 the 7th ID had moved to Fort Lewis, Washington. As part of the post-Cold War reduction of forces, the 7th Infantry Division (Light) was deactivated on June 16, 1994 at Fort Lewis.

Since the end of the Cold War, the US Army has considered new options for integrating the components of the Active Army, National Guard, and Army Reserve. To facilitate the training and readiness of National Guard units, two active duty division headquarters were activated. The 7th ID was one of these, reactivated on June 4, 1999, at Fort Carson, Colorado. While the active division headquarters concept worked admirably, a new component called Division West under First Army was activated to control the training of reserve units in 21 states. This made the need for the active component headquarters obsolete and the 7th Infantry Division headquarters was deactivated for the final time on August 22, 2006.

The 7th Infantry Division was identified as the highest priority inactive division in the US Army Center of Military History's lineage scheme due to its numerous accolades and long history. All of the Bayonets' flags and heraldic items are located in the National Infantry Museum at Fort Benning, Georgia.